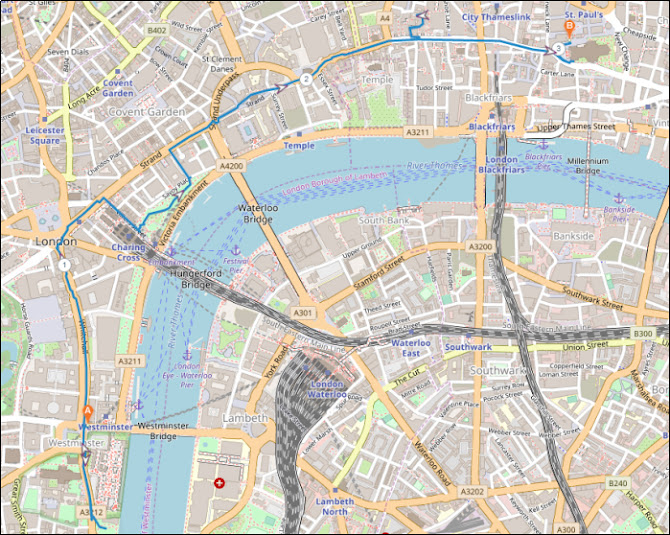

Walk 18 - A Trail of Two Cities - A walk from the City of Westminster to the City of London

Approximately 3 Miles / 4.9 Km - about 2 hours.

The walk starts at Westminster Tube Station and ends at St Paul’s Tube Station.

An online, zoomable version of the above map can be accessed at www.plotaroute.com/route/1820068

INTRODUCTION & OVERVIEW

This walk follows an historic route between two very old cities, Westminster and London. It starts at Westminster, once long ago the damp Thorney Island, which was formed by rivulets of the River Tyburn flowing towards and into the River Thames. It is now the location of Westminster Abbey and the Houses of Parliament.

This walk approximately follows the old route taken by royalty when visiting the City of London, which was first walled by the Romans.

The walk goes up Whitehall, then right along the Strand and Fleet Street. It enters the old City of London at Newgate, and finishes at St Paul’s Cathedral on Ludgate Hill, which has been the site of a church since 604 AD.

All along the route there are historic buildings and ancient sites which will be described as you pass them.

Leave the station via Exit 4 (Bridge Street North), turn right and then turn left to cross over Bridge Street at the pedestrian crossing, heading towards the Houses of Parliament. Turn right and walk left around the corner, keeping the Parliament fence on your left.

Over the road in Parliament Square Garden, the nearest statue is of Winston Churchill which was erected in 1973. Among other statues in this garden are depictions of David Lloyd George, Benjamin Disraeli, Sir Robert Peel, Nelson Mandela and Mahatma Gandhi.

Carry on walking, and stop when you get to the building with the two square towers and the flying buttresses, on the left behind the fence.

THE PALACE OF WESTMINSTER

In the 1040s King Edward, (later called Edward the Confessor), one of the last

Anglo-Saxon English kings, built the first Palace of Westminster here.

Westminster Hall - IMAGE CREDIT GOOGLE EARTH

George IV's coronation banquet held in Westminster Hall in 1821

PUBLIC DOMAIN IMAGE

The rest of the Parliament buildings are much younger. Apart from Westminster Hall, and the Jewel House, which we will look at later, the other buildings were mostly lost in a fire in October 1834.

In 1836 Charles Barry, in collaboration with Augustus Pugin, won a design competition for a new Palace of Westminster. They used a Gothic Revival syle. The new buildings took up until 1870 to be finished. These are the buildings that you see here now.

Carry on walking past Westminster Hall on Parliament Square as it turns into St Margaret Street. On the left, behind the fence, you will pass a statue of Oliver Cromwell.

Further on is St Stephen’s Hall, the entrance which is used by visitors who are attending a debate or a committee meeting.

After St Stephen’s Hall there is a space, now used for parking, called Old Palace Yard. In it there is a equestrian statue of Richard the Lionheart (Richard I of England).

Victoria Tower - Sovereign's Entrance

Walk a little further on and turn left into the Victoria Tower Gardens South.

THE BURGHERS OF CALAIS

You first see a statue of Emmeline Pankhurst (1858-1928), the suffragette and women's rights activist. The statue depicts her in middle age, standing as if addressing an audience.

Go further into the park and you will see another sculpture, The Burghers of Calais by Auguste Rodin. The original sculpture was made in 1889 to stand outside Calais town hall. Rodin later made four casts of the original, this is one of them. It was purchased in 1911, and Rodin himself visited London to give advice on where it should be located. It was erected here shortly afterwards.

The statue depicts a scene in 1346, when King Edward III of England laid siege to Calais.

The Burghers of Calais by Auguste Rodin

The Burghers of Calais by Auguste RodinReturn the way you came, along St Margaret Street. Over the other side of the road you will first come to The Jewel Tower, an old, square, three storey stone building with norman-romanesque (rounded top) windows.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=965022

A little further on, also on the other side of the road, you will come to Westminster Abbey.

WESTMINSTER ABBEY

Near to the original Westminster Palace was a small Benedictine monastery, previously built in around 960 AD. Edward the Confessor enlarged the monastery, and built a large stone church in the 11th century as part of it. It was named ‘St Peter the Apostle’ and was built on the site of a previous Saxon Church .

The St Peter the Apostle church became known as the “west minster” to distinguish it from St Paul’s Cathedral in the City of London, which was sometimes referred to as the “east minster”. The formal name of the current Westminster is still the “Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster”

Edward the Confessor’s church was demolished and rebuilt as Westminster Abbey in the mid 13th century by Henry III.

The part of Westminster Abbey that is closest to you now is called “The Henry VII Lady Chapel”. In it are buried fifteen kings and queens. These include Henry VII, Elizabeth I, Mary I, Mary Queen of Scots, George II, Charles II, William III and Mary II, and Queen Anne.

The Henry VII Lady Chapel

The Henry VII Lady ChapelContinue on and re-cross over Bridge Street. Now begin to walk up Parliament Street, towards Whitehall.

As you walk up Parliament Street, you pass a number of government offices. At the beginning of Parliament Street, on the left you pass the Treasury and the Foreign Office.

Soon you will come to the Cenotaph in middle of the road. Here Parliament Street becomes Whitehall.

THE CENOTAPH

The Cenotaph was designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens, and was made from Portland stone. It was unveiled here on the 11th November 1920. Cenotaph means 'empty tomb' in Greek. It has become a focus for national commemoration, and a place for mourning all those who died as a result of war.

Walking on, next you will pass Downing Street on the left.

DOWNING STREET

Downing Street holds the official residence and offices of the Prime Minister and the Chancellor of the Exchequer. It was built in the 1680s by Sir George Downing, who employed Sir Christopher Wren to design the houses.

The first British Prime Minister to live at 10 Downing Street was Sir Robert Walpole, who moved into it in 1735 after a three year rebuild. The building had been purchased by King George II for the use of ‘The First Lord of the Treasury’, the official title of the post of Prime Minister.

Just past Downing Street, in the middle of Whitehall, is the Monument to the Women of World War II

MONUMENT TO THE WOMEN OF WORLD WAR II

Unveiled July 2002, the Monument celebrates the many different jobs that women took on in World War II to keep the ‘home front’ working.

The lettering used on the monument uses the typeface that was used on war time ration books. The sculpture of sets of clothing and uniforms around the sides of the monument symbolise the types of jobs that the women took on, and the fact that they are hanging up symbolises that the jobs were given back to the homecoming men when the war ended.

A little further up Whitehall on the right are three statues of three World War II Field Marshals. They stand outside the Ministry of Defence Main Building.

THREE WORLD WAR II FIELD MARSHALS

The three statues are of Field Marshal Montgomery, Field Marshal Alan Brooke and Field Marshal Slim.

Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery (1887-1976), was nicknamed "Monty". Monty saw action and was wounded in World War I. He held a number of high level army command positions during World War II, including commander of the British Eighth Army from August 1942. He was much admired as a commander, but by some was thought to be lacking in tact and a little boastful on a personal level. Winston Churchill, the Prime Minister during World War II, was a good friend of Montgomery. However, he is quoted as saying about Monty, "In defeat, unbeatable; in victory, unbearable.”

Field Marshal Alan Francis Brooke (1883-1963) was a senior officer in the British Army. During World War II, he was Chief of the Imperial General Staff, the professional head of the British Army. Brooke was promoted to Field Marshal in 1944. Brooke became the chair of the Chiefs of Staff Committee, so was the chief military advisor to the Prime Minister..

Field Marshal William Joseph Slim (1891-1970) was known as "Bill Slim”. Slim saw active service in both the World Wars I and II. He was wounded in action three times.

During the Second World War he led the 14th Army in the Burma campaign.

After the war he was appointed Chief of the Imperial General Staff, and from 1953 to 1959 became Governor-General of Australia.

Continue on up Whitehall, past an equestrian statue in the centre of the road depicting Earl Haig.

FIELD MARSHAL DOUGLAS HAIG

During the World War I, Field Marshal Douglas Haig, commanded the British Expeditionary Force on the Western Front from 1915 until the war ended in 1918. He was commander during a number of major battles, including the Somme, Arras, and Passchendaele.

Since the 1960s, Earl Haig’s leadership and battle strategies in World War I have come under fierce criticism, because of the number of casualties that resulted.

A little further up Whitehall, you will come to the Banqueting House on the right.

PALACE OF WHITEHALL

This area, on both sides of Whitehall, is the site of the Palace of Whitehall. It was originally called York Place because it was the original London home of the Archbishops of York.

The Old Palace of Whitehall by Hendrik Danckerts 1673

The Old Palace of Whitehall by Hendrik Danckerts 1673PUBLIC DOMAIN IMAGE

During the reign of Henry VIII, the then Archbishop of York, Cardinal Wolsey, fell out of favour with the King and had York Place taken from him.

Henry started improving and enlarging York Place, to make it into a royal palace for himself and his queen, at that point Anne Boleyn. Renamed Whitehall, it became Henry’s main Palace that he ruled from. The Palace lasted until 1698, in the reign of William III, when the palace caught fire and burnt down.

THE BANQUETING HOUSE

The current Banqueting House was commissioned by King James I. It was designed by Inigo Jones, the Surveyor of the Kings Works, and finished in 1622. Inigo Jones had previously travelled in Europe, where he took a great interest in the Classical architecture of Ancient Rome and the Renaissance. This was a great influence on his design for the Banqueting House. King James used the building for holding masques, which were court entertainments with music, dancing, singing and acting.

The Banqueting House

The Banqueting HouseTHE EXECUTION SITE OF CHARLES I

English Civil War saw military and political battles between the parliamentarians and the royalists. As a result of this struggle, King Charles I was captured by the parliamentarians.

There was a trial in Westminster Hall (which we saw earlier), conducted by the parliamentarian High Court of Justice, and Charles was found guilty of "...upholding in himself an unlimited and tyrannical power to rule according to his will, and to overthrow the rights and liberties of the people.".

He was sentenced to death by beheading.

The execution of Charles I outside the Banqueting House

The execution of Charles I outside the Banqueting HousePUBLIC DOMAIN IMAGE

Before the execution, which was to take place on a scaffold built outside the Banqueting House, Charles asked for an extra shirt. He said this was so that the crowd wouldn’t see him shiver from the cold and mistake it for cowardice. On the 30th January 1649, after giving a speech to the crowd, Charles I was executed .

A little further up Whitehall, over the road from the Banqueting House, is the Whitehall entrance to the Horse Guards building.

THE HORSE GUARDS BUILDING

There are usually two mounted soldiers here at the entrance, which leads to the Household Cavalry Museum, Horse Guards Parade, St James’s Park and Buckingham Palace. It also leads to the headquarters of the Household Cavalry Mounted Regiment, who provide troops for The Queen's Life Guard.

There has been a guard kept here since 1660. At that time the original Guard House of the old Palace of Whitehall was here. The Palace of Whitehall was the biggest palace in Europe at that period. The Palace burned down in 1698. The current Horse Guards building was built in 1753.

Continue walking up Whitehall. Turn right into Whitehall Place and walk a little way down the left side to the Blue Plaque on the wall, marking the site of the original Scotland Yard.

The original headquarters of Scotland Yard

The original headquarters of Scotland YardThe Metropolitan Police was formed by Robert Peel in 1829. He chose 4 Whitehall Place, formerly a private house, for the new police headquarters. The building backed on to Great Scotland Yard, also branching off Whitehall. In 1890, because the Metropolitan Police needed more space for an enlarged force, they moved to a new building, called ‘New Scotland Yard’ on the Victoria Embankment. The name was a reminder of the original building.

After a few moves within the Victoria area, and redesigns and rebuilds in the intervening years, New Scotland Yard is now back on the Victoria Embankment.

Continue walking down Whitehall Place, then turn first left into Scotland Place. As you get to the junction with Great Scotland Yard (the rear of the original Scotland Yard building) facing you is a building that is still used as a police horse stables.

Turn left into Old Scotland Yard, then turn right to get back on to Whitehall.

Continue to just before where Whitehall terminates at Trafalgar Square. In the middle of Whitehall is a small island with a statue of Charles I mounted on a horse. Cross over on the crossings to the island.

EQUESTRIAN STATUE OF KING CHARLES I

The original Charing Cross monument, The Eleanor Cross, one of 12 decorated crosses erected to commemorate Queen Eleanor, once stood on the spot that this statue now stands.

Statue of Charles I - Original Site of an Eleanor Cross

Statue of Charles I - Original Site of an Eleanor CrossWhen Queen Eleanor died in Harby (Nottinghamshire) in 1290, her husband of 36 years, King Edward I (also known as Edward Longshanks), decided to bring her body back to London for interment in Westminster Abbey. To commemorate his wife, Edward had large decorated stone monuments, all topped with a cross, erected at each place that they had stopped with the body on the journey to Westminster. These places were: Lincoln, Grantham, Stamford, Geddington, Hardingstone, Stony Stratford, Woburn, Dunstable, St Albans, Waltham (now Waltham Cross), Cheapside and Charing.

‘Charing’ was the name of a village here, thought to be a corruption of ‘La Chère Reine’ meaning ‘The Dear Queen’. There is discussion about if this refers to Queen Eleanor or the Virgin Mary, as the area was already called Charing before 1290. Another idea is that the name Charing came from the old English word 'cierring', which meant 'turning', either referring to he curve in the River Thames near here, or this turning point in the road when journeying between the cities of Westminster and London.

The Eleanor Cross was taken down during the English Civil War, and was eventually completely demolished in 1647.

A ballad from that period ran:

Undone! undone! the lawyers cry,

They ramble up and down,

We know not the way to Westminster,

Now Charing-Cross is down.

After the restoration of the monarchy, Charles II commissioned this statue of his father Charles I, which was put on the original site of the Charing Cross.

From the statue you can look west south-west towards the curved Admiralty Arch, beyond which is the Mall and Buckingham Palace. To the North is Trafalgar Square, with Nelson’s Column in the middle. Beyond Nelson's Column is The National Gallery. To the right of the square is St Martin's in the Fields Church.

ADMIRALTY ARCH

The Admiralty Arch was commissioned by King Edward VII as a memorial to his mother, Queen Victoria. It was designed by Aston Webb, and completed in 1912. It is a Grade I listed building. It was used by the Admiralty, and has been used as residence of the First Sea Lord. It has also been used as government offices. A 125 lease for the building was sold in 2012 for £60m. It is now being developed into a hotel and luxury apartments by the Waldorf Astoria group.

TRAFALGAR SQUARE

Up until the early 19th century this area was known as Charing Cross (see above for origin of name). It was the site of the Royal Mews from the 14th century, where the royal hawks were kept. The name ‘Mews’ derives from the word they used to describe moulting, as the hawks were confined there when they shed their feathers. In the 16th century the building they kept the birds in was rebuilt as stables. In the 18th century the Royal Mews were rebuilt once more, this time as a grand stone building.

In the 19th century, after King George IV had moved the mews to Buckingham Palace, the area was rebuilt by John Nash, as Trafalgar Square. It was to be a commemoration of the victory at the Battle of Trafalgar, which took place on 21st October 1805 off the coast of Cape Trafalgar (about 30 miles west of Gibraltar). It opened in 1844, with the centrepiece being the 51.59 metre Nelson’s Column. On top of the Corinthian column is a statue of Admiral Horatio Nelson, who commanded the British fleet and who died of his wounds at Trafalgar. After the battle, Nelson's body was put into a cask of brandy mixed with camphor and myrrh for preservation. HMS Victory, which had been damaged, was towed back to England carrying the body. Nelson was interred in the crypt of St Paul’s Cathedral within a marble sarcophagus that was originally made for Cardinal Wolsey .

ST MARTIN IN THE FIELDS

St Martin in the Fields church faces Trafalgar Square. It has a spire, and stands on the right of the Square if you are viewing it from the Charles I statue. There has been a place of worship on the site of St Martin since the Roman period (and perhaps before). A 2006 archaeological excavation beneath the church uncovered a Roman grave from around 410 AD.

There have been a number of churches dedicated to St Martin on the site since. Henry VIII rebuilt the church in 1542 so that plague victims from the local the area didn’t have to pass through his Palace of Whitehall. The church’s name derives from the time that it actually was surrounded by fields at this time, sitting between the cities of Westminster and London. The current church was opened in 1724.

The crypt beneath St Martin in the Fields is a good place for a break if you are in need of something to eat or drink. There are toilets here too.

From the island that the Charles I statue stands on, use the crossings to get to the Strand, and walk east to the front of the Charing Cross Station and Hotel on the right.

CHARING CROSS STATION AND HOTEL

In the forecourt of Charing Cross station and the Charing Cross Hotel is a larger (21 metres high) and more ornate version of the original Eleanor Cross. It was erected in 1865 and was commissioned for the newly opened Charing Cross Hotel by the South Eastern Railway Company.

19th Century print of the replica Charing Cross, in front of the hotel and station

19th Century print of the replica Charing Cross, in front of the hotel and stationPUBLIC DOMAIN IMAGE

The design of the Albert Memorial is thought to have been inspired by the Eleanor Crosses.

Before Charing Cross station and Hotel were built in 1864, the area housed the Hungerford Market. This was a produce market, first built in 1682, then rebuilt in 1832. The market had replaced the site of Hungerford House, the town house of the Hungerford family. This house burned down in 1669, which was recorded in the Diary of Samuel Pepys.Continue walking along The Strand and turn right down Villiers Street, which goes down towards the Thames along the side of the Charing Cross Hotel.

This street is named after George Villiers, the 1st Duke of Buckingham and an owner of York House, which stood in this area.

Before you get to Embankment Underground Station, turn left into Victoria Embankment Gardens. On the left is the York Watergate.

YORK WATERGATE AND THE GRAND HOUSES ON THE STRAND

The word ‘strand’ comes from Old English, meaning a shore of a sea, river or lake. Originally, the Thames was wider here and the Strand ran along the north bank of it.

The York Watergate

The York WatergatePhoto by lonpicmen Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported

The York Watergate was the gate leading down to the Thames from the gardens of York House. Before the Victoria Embankment (stretching from the Palace of Westminster to Blackfriars Bridge) was built between 1865 and 1870, the Thames was much wider here, and came up to this watergate.

York House, formerly Norwich Place, was so named when it was granted to the Archbishop of York in 1556. In the 1620s it was acquired by George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham, a favourite of James I and said to be his lover.

Some of the other grand houses built along the Strand included:

Some of the grand houses along the Strand - 1560's Agas Map

Some of the grand houses along the Strand - 1560's Agas MapCecil House. First called Exeter House or Burghley House, Cecil House was built in the 16th century by William Cecil. It was sited on the north side of The Strand.

Durham House, the London townhouse of the Bishop of Durham.

Essex House. Originally called Leicester House, it was built around 1575 for Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester

Savoy Palace was owned by John of Gaunt until it was destroyed in riots in 1381 during the Peasants' Revolt.

Somerset House, which is still there, is a Georgian quadrangle, built and extended in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. It was built on the site of a palace which was originally owned by the Duke of Somerset.

Walk east through the park, parallel with the river, until you get to the statue of Robert Raikes, the founder of Sunday Schools. Turn left here and walk north, away from the river to the park exit there. Straight ahead is Carting Lane. Walk up it towards the Strand, going past the Savoy Hotel, and then the Savoy Theatre on your right.

CARTING LANE

The original name of Carting Lane was Dirty Lane. In the 19th century the name was changed as it was thought to be too rude.

CARTING LANE LAMPS

On the side of the Theatre, and also further up where Carting Lane meets the Strand, there are some replica gas lamps. In Victorian times the lamps here were fed with Sewer Gas (methane), giving Carting Lane an unusual aroma. This led some of the ruder locals to give it the nickname “Farting” Lane!

Walk up the steps, past The Coal Hole pub to the Strand.

THE COAL HOLE PUB

The Coal Hole is so named because the site was once the coal cellar for the Savoy Hotel.

Turn right along the Strand. You will pass the entrance to the Savoy Hotel.

THE SAVOY HOTEL AND THEATRE

Henry III granted the land to Count Peter of Savoy in 1246. (The golden figure above the Savoy Hotel sign is a representation of Count Peter).

In the 14th century, John of Gaunt, the son of King Edward III, built the Savoy Palace here, one of the largest and grandest palaces along the Strand.

In 1381, during the Peasant’s Revolt, a mob burned down the palace.

In the early part of the 16th century, Henry VII had a hospital built here. The hospital lasted until the early 18th century and most of the buildings were finally demolished in the early 19th century when the Waterloo bridge was built.

There is part of the hospital that still remains, the Chapel of St John the Baptist, also called the Queen’s Chapel of the Savoy.

The Savoy Hotel and Theatre was first opened in 1889. Theatrical impresario Richard D’Oyly Carte, known as the backer behind Gilbert and Sullivan’s first operettas, was the man who built the Savoy. It was the first purpose-built deluxe hotel in London.

The Savoy Hotel and Theatre

The Savoy Hotel and TheatreThe hotel has frequently had design updates, and in the mid 1920’s the Art Deco design which is still apparent was introduced.

If you want to see the remaining part of the 16th century hospital, the Queen’s Chapel of the Savoy, as you continue walking along the Strand, on past the Savoy Hotel, turn first right into Savoy Street. Walk down about 35 metres and you can see the Queen's Chapel on the right.

Return back up Savoy Street and turn right to continue walking east along the Strand.

You will then get to Lancaster Place. Before you cross over it, look to the right to get a view of the side of Somerset House facing Lancaster Place.

The side of Somerset House facing Lancaster Place

The side of Somerset House facing Lancaster PlaceIf you look left to over the other side of the Strand, you can see where Aldwych branches off in a curve.

The Aldwich

The AldwichALDWYCH

After the Romans left Britain in the 5th century, Londinium (within the London City walls) emptied.

By the 7th century the Anglo Saxons had set up a major settlement called ‘Lundenwic’, meaning 'London dwelling place'. This was west of Londinium in the area that we now know as the Strand, which they used for boat fishing and trading.

The Saxons called the area within the Roman walls ‘Lundenburh’ meaning 'London fortified settlement'.

Probably due to Viking raids, the Anglo Saxons started to move back inside the city walls, and their trading and fishing fleets moved from the Strand area to the mouth of the River Fleet. Alfred the Great repaired the London walls in the late 9th century.

After the Anglo Saxon population had moved into Lundenburh (the Roman walled area), Lundenwic (the Strand area) became known as ‘ealdwic’ meaning the ‘old dwelling place’. The name was documented as ‘Aldewich’ in 1211. From this we get the name of the area now called the Aldwych.

Cross Lancaster Place and carry on walking down the Strand. On the right you will pass the arches leading to the courtyard and the Strand entrance of Somerset House.

SOMERSET HOUSE

The original Somerset House was built in the 16th century by Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset, and the eldest brother of Jane Seymour, Henry VIII’s third wife. When Henry died, and his 10 year old son Edward became King Edward VI, a Council of Regency was formed to guide the young king. There were power struggles within the council, and John Dudley, the Earl of Warwick, became it’s leader, ousting Edward Seymour. Edward unsuccessfully tried to counter this to regain power himself. The result was that Edward Seymour was executed in 1552 for ‘felony’, which meant trying to change of government. Somerset House then came into the possession of the Crown.

View of the courtyard of Somerset House

View of the courtyard of Somerset House The Somerset House Conference (artist unknown)

The Somerset House Conference (artist unknown)PUBLIC DOMAIN IMAGE

Somerset House was also Anne of Denmark’s (James I’s wife) residence in London, and where James I’s body lay in state.

During the English Civil War the building was used as the Parliamentarian army headquarters. It’s commander-in-chief, General Fairfax, had his quarters there, as did a number of other Parliamentarian leaders.

After the Restoration, it was the residence of Queen Henrietta Maria (wife of Charles I), Catherine of Braganza (wife of Charles II) and was extended and refurbished. During the late 17th and the first three quarters of the 18th century, the condition of the building deteriorated and lost it’s royal connections. It was demolished in 1775.

The current Somerset House was built in the Palladian style as a public building. It took a long time to construct, and was finally completed in the early 19th century.

It has been, and in some cases still is, the home of a number of organisations. These include, the Royal Academy, the Royal Society, the Society of Antiquaries, the Royal Astronomical Society, the Government School of Design. Organisations within the navy have used it, including the Navy Board, the Victualling Commissioners, the Sick and Hurt Commissioners, the Navy Pay Office and the Admiralty Museum. It has also been used by the Inland Revenue and the Tax Office as well as the Registrar General of Births, Marriages and Deaths and many other government departments and public bodies.

Continue along the Strand until you get to the church of Mary le Strand.

St Mary le Strand

St Mary le StrandST MARY LE STRAND

This is the second St Mary Le Strand church. The current St Mary le Strand was the first of twelve new churches to be built in London by the ’Commission for Building Fifty New Churches’. The church opened on the 1st of January 1724. The Commission was putting into practice a new act of parliament which aimed to build fifty new churches using income which was still being collected from the tax on coal arriving in London. This tax had been instigated after the Great Fire of London in 1666, to pay for rebuilding churches and public buildings that had been burnt down.

The maypole shown in George Vertue's engraving of a 1713 procession along the Strand

The maypole shown in George Vertue's engraving of a 1713 procession along the StrandIn 1717, Sir Isaac Newton purchased the maypole, and transported it to the grounds of Wanstead House, then owned by Sir Richard Child. It was used to support a telescope, then the largest in the world. The astronomers were James Bradley and his uncle James Pound, the curate and rector of St Mary’s Church in Wanstead, and both keen astronomers.

On the north side of the church is a rear entrance into Bush House.

BUSH HOUSE

Bush House was the headquarters of the BBC World Service, which broadcast programmes from there from 1941 to 2012. Since 2015 King's College London has leased the building as part of its Strand Campus.

Rear Entrance to Bush House

Rear Entrance to Bush HouseWalking further along the Strand, you will come to St Clement Danes church.

ST CLEMENT DANES

St Clement Danes, is one of two churches claiming it's the St Clements in the “Oranges and Lemons” childrens’ song (the other is St Clement’s Eastcheap). It has bells which play the tune. It is a Wren church, built in 1682, and is currently the central church of the Royal Air Force. Outside the church are two statues of wartime RAF leaders, Hugh Dowding and Arthur "Bomber" Harris.

Continuing along the Strand, you will come to The Royal Courts of Justice.

ROYAL COURTS OF JUSTICE

The Royal Courts of Justice house the High Court and Court of Appeal of England and Wales.

These courts deal mainly with Civil Law, such as commercial disputes, inquests and divorce proceedings. Criminal courts such as the Old Bailey, take the criminal cases. The Royal Courts are also courts of appeal, and take both criminal and civil appeals.

Royal Courts of Justice

Royal Courts of JusticeOriginally these Royal Courts were based in Westminster Hall, which we saw as part of the Houses of Parliament. However, during the 19th century, it was decided that a new purpose built structure was needed.

The six acre site that the Courts now stand on was purchased for £1,453,000, and George Edmund Street won a design competition for the new courts. The building work started in 1873, but strikes disrupted the building work. Foreign workers were bought in, which created much hostility from the strikers. To protect the foreign workers, they had to be housed and fed within the building itself. The disputes were eventually settled, but it took eight years for the building to be completed. In 1882, the courts were finally opened by Queen Victoria.

Opposite to the Royal Courts of Justice is Twinings Tea Shop.

TWININGS TEA SHOP

This is one of the oldest shops in London. Thomas Twining bought a Coffee House in the Strand in 1706, and gradually converted it to selling tea, as it became more fashionable. He also began selling the dried tea leaves for people to make tea at home. The current entrance was built in 1787. Having the Golden Lion on the top of the doorway dates from a time when there were no streets numbers and shops identified themselves by having a symbol above the door. Thomas Twining chose the lion.

TEMPLE BAR MEMORIAL

In the middle ages, the City of London expanded its jurisdiction beyond the City Walls out to 'Bars'. Bars were gates erected across roads, to regulate and tax trade in and out the City of London. Temple Bar was one of these, and so named as it was in an area that was originally owned by the Knights Templar.

Temple Bar became a ceremonial entrance into the City of London from the City of Westminster. It has often been a traditional place for “The Ceremony of the Pearl Sword”. This is played out when the monarch officially visits the City. The ceremony consists of the Lord Mayor of the City of London meeting the monarch at Temple Bar (or where it used to be). The monarch is then ceremonially welcomed, and the Lord Mayor offers the hilt of a pearl handled sword. The monarch then touches the sword before entering the City. The process is a ceremonial “surrendering” of the Lord Mayor’s weapon to the monarch.

Temple Bar Gate in 1870, when it was still located to mark the Temple Bar

Temple Bar Gate in 1870, when it was still located to mark the Temple BarPUBLIC DOMAIN IMAGE

Carry on walking in the same direction, until Chancery Lane joins from the north.

CHANCERY LANE

Originally built around 1160, what we now call Chancery Lane was owned by the Knights Templar, and was called New Street. Ralph Neville, the Bishop of Chichester and Lord Chancellor of England, built a palace on land in New Street given to him by Henry III in 1227. This became known as the Chancellor’s Palace. After that, New Street began to be referred to Chancellor Lane, which finally became called Chancery Lane.

On the opposite side of the road to Chancery Lane is a black gate leading to Temple Church and the Inner Temple.

Gateway to the Inner Temple

Gateway to the Inner TempleThe Inner Temple is one of the four Inns of Court. The Inns are professional

associations for barristers and judges, and the name derives from the fact that the Knights Templar owned the land it’s on before they were abolished in 1312.

Continue walking up Fleet Street. On the left is the church of St Dunstan in the West. Cross over the road to it. High up on the right of the church front is a statue of Queen Elizabeth I.

LUDGATE STATUE OF QUEEN ELIZABETH IThe statue is 16th century and pre-dates the church itself, which was built in the early 19th century. It is part of the remains of the Ludgate on which it was displayed. There is another statue that was also part of the Ludgate. This is of ‘King Lud and his sons’, and is in the church porch. However, this is not currently viewable by the public.

We will be coming to the site of the Ludgate at the end of Fleet Street.

Continue along Fleet Street, cross Fetter Lane, pass Red Lion Court on the left, and then turn left into Johnson’s Court. Continue along as it bends right and left, until you get to Dr Johnson’s House in pedestrianised Gough Square. Outside the house, in the square, there is a statue of Johnson’s cat, “Hodge”.

Doctor Johnson's House

Doctor Johnson's HouseJohnson’s House is open to the public. See drjohnsonshouse.org

Follow the Johnson’s Court route that you came up, back to Fleet Street. Then turn left and continue along Fleet Street until you get to Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese Pub on the left.

YE OLDE CHESHIRE CHEESE

There has been a pub here since 1538, and Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese was rebuilt after the Great Fire. There is not much natural lighting inside the pub, and it has lots of old wood panelling, which gives it an old and cosy atmosphere. There are a number of bars and other rooms inside, with open fires in the winter.

Beneath the pub are old vaulted cellars, pre-dating the rest of the building. As there was a Carmelite monastery on the site, which dated from the 13th century, it is thought that the cellars could have been part of that.

Walk a short distance further along Fleet Street to the Art Deco stone building on the left, with a large blue-faced clock.

NEWSPAPER BUILDINGSFleet Street was once home to many newspaper offices, with printing presses at the rear. These have mostly now moved to locations further out of the city which are better suited to modern newspaper production, technology and transport.

The Telegraph and Express buildings in Fleet Street

The Telegraph and Express buildings in Fleet StreetJust opposite to the Express building, on the other side of Fleet Street, is St Bride's Avenue. If you look down it you will catch a glimpse of St Bride's Church.

St Bride's Church

St Bride's Church Fleet Street, where the street dips as it crosses Farringdon Street

Fleet Street, where the street dips as it crosses Farringdon StreetFARRINGDON STREET / THE RIVER FLEET

You can see, as to walk towards where Farringdon Street crosses Fleet Street, there is a dip. This is because Farringdon Street follows the path of the River Fleet, flowing down to the Thames. Where Fleet Street meets Farringdon Street is called Ludgate Circus. There was once a bridge across the Fleet here. After crossing the bridge, travellers to the City of London would have continued up Ludgate Hill as it rises towards St Paul’s.The Fleet is now underground in sewer pipes, but was once the largest of the London rivers flowing into the Thames. The Fleet rises as two streams on Hampstead Heath, which in the 18th century were dammed to create the Hampstead and Highgate collection of ponds.

Walk down to Ludgate Circus.

Ludgate Circus

Ludgate CircusTHE RIVER FLEET

From here, you can look left up towards Holborn, and see the slope that the Fleet flowed down towards the Thames.

The River Fleet, in this area, was also once called the Oldbourne (meaning old stream). This is how the Holborn area got its name.

In Anglo-Saxon times, the Fleet was a medium sized river. It’s mouth, where it joins the Thames, was used to moor their boats after they moved into the walled city of London from the Aldwych (meaning old dwelling place).

A number of wells were dug near the Fleet, giving names to places like Bridewell and Clerkenwell. Unfortunately, in later years, and right up to Victorian times, the Fleet got used more and more as a sewer, and a dumping place for rubbish and dead animals.

Walk across Ludgate Circus, and up Ludgate Hill towards St Paul’s Cathedral. Pass Limeburner Lane on the left.

LIMEBURNING

Limeburning, the trade that gave Limeburner Lane its name, was burning limestone in a kiln. This produced Lime to be used in plaster, mortar, and other building materials.

Walk on, passing Old Bailey on your left.

OLD BAILEY

The word Bailey refers to an outer wall of a fortification. The Roman and Medieval London Wall ran in the same direction as Old Bailey, and a little way to the east of it. The street called Old Bailey is home to the Central Criminal Court, also known as the Old Bailey. There have been courts of various types on this site since at least 1585. The courts were next to Newgate Prison, which originally dated from the 12th century, and finally closed in 1902. Newgate Prison got it’s name because the Newgate, in the London Wall, was near it at it’s north side.

Walk a little further up Ludgate Hill towards St Paul’s, until you get to St Martin Within Ludgate church.

ST MARTIN WITHIN LUDGATE

The church name indicates that it is sited just inside the Ludgate in the London Wall, which went roughly north from here, up to the Newgate.

The current church here was, like many other City churches, rebuilt by Christopher Wren after the Great Fire of London in 1666. There was a church on the site for many years before this. The parish books start in 1410, but there is reputed to have been a religious building on the site in the seventh century, when Cadwallon ap Cadfan, the King of Gwynedd, was buried here after a battle.

Walk on up to St Paul’s Cathedral. Enter the gate on the right hand side of the entrance steps.

St Paul's Cathedral and the pavement showing the old and new cathedral floor plans

St Paul's Cathedral and the pavement showing the old and new cathedral floor plansST PAUL’S CATHEDRAL

OLD & NEW PLAN

As you can see on the plan, the pre-fire Medieval St Paul’s was slightly larger that it’s replacement, and was built at a slightly different alignment. The altered alignment may be to do with the changes in magnetic north over time, from which the traditional East facing alignment of the altar end of churches is calculated.

The Medieval St Paul’s was begun in 1087 and consecrated in 1240. It’s thought possible that there were at least two predecessors to the Medieval St Paul’s on the site, although absolute evidence for this is unclear.

Walk back around, past the front steps of St Paul’s to Temple Bar Gate.

Temple Bar Gate

Temple Bar GateAs mentioned previously, when we passed the original site of Temple Bar near the Royal Courts of Justice, “Bar’s” were set up around the City of London in the middle ages to expand its jurisdiction beyond the city walls. The Temple Bar in the Strand was first documented in 1293, although it wouldn’t have been as grand as this one, probably it was a wooden bar or a chain across the road. Through the years, grander Temple Bars were built. This one was built by Christopher Wren just after the Great Fire, although the previous wooden one hadn’t been damaged.

END OF WALK

That is the end of the walk. There is a public toilet in Paternoster Square, just through the Temple Bar Arch. There are also a number of coffee shops in the area and a Young’s pub, “The Paternoster” which does food. To get to the pub, enter Paternoster Square, turn right, then turn first left into Queens Head Passage.

The nearest tube station is St Paul’s.

To get to the tube, enter Paternoster Square, turn right, pass Queens Head Passage and turn left into Panyer Alley.

Send us your feedback!

Link to feedback form

Let us know if you enjoyed the walk and if you have any other feedback we could use to improve it.

Russell & Paul